A lot of people have heard the story of the “first Thanksgiving,” and can vividly picture images of Native Americans breaking bread with “the Pilgrims.” But how much do you know about the history of this holiday and the specific people who were involved in what is generally regarded as the first Thanksgiving meal?

What is Thanksgiving?

If you’re not from the US, you might be unfamiliar with the practice of Thanksgiving. The American version of the holiday takes place on the fourth Thursday in November. There are similar observances around the world, but the American one is unique for being the originator of the practice.

American Origins

The “first Thanksgiving,” as many Americans call it, was a meeting between English colonists living at Plymouth and the Native American Wampanoag tribe in 1621. The two groups shared an autumn feast ahead of the harsh winter, eating up their food reserves before everything spoiled in the cold.

Plymouth Settlers

In late 1620, a ship named the Mayflower set out from Plymouth, England with 102 religious separatists who wanted to escape persecution at the hands of the Church of England set out for what they called the “New World.” There were already European colonizers in the Americas at the time, but the Plymouth pilgrims, as they were known, have entered American history as a specifically recognizable group.

Landing in the Americas

The Mayflower landed near the edge of Cape Cod after 66 arduous days at sea. They intended to make landfall near the Hudson River, and it took them another month to make their way across the Massachusetts Bay and establish the beginnings of a settlement they’d also name Plymouth.

Harsh Winter

In the winter of 1620, the pilgrims suffered heavy losses due to exposure to the elements and outbreaks of disease. Many of them stayed on the Mayflower as a form of shelter, and only around half of the original number survived until March of 1621. When the cold weather finally abated, they moved inland and met an Abenaki Native American who spoke English.

Squanto

The Abenaki tribesman introduced the pilgrims to a Pawtuxet man named Squanto, who had survived being kidnapped by Englishmen and sold into slavery in London. Squanto had escaped this horrible ordeal and returned home to his tribe, and had learned English over the course of his enslavement.

Teaching them How to Survive

Squanto, feeling moved by the pilgrims’ plight, taught the starving, malnourished Europeans how to catch fish, raise corn, and even gather sap from maple trees. He went above and beyond, even helping the Europeans establish peaceful relations with the nearby Wampanoag tribe.

An Unlikely Alliance

The 50 years of peaceful cohabitation between the Wampanoag and the Plymouth settlers remains one of the few genuinely positive interactions between a tribe and a large European settlement. Sadly, elsewhere in the Americans, European settlers ranged from indifferent toward Native Americans to outright hostile.

The First Thanksgiving

After the pilgrims learned how to survive thanks to Squanto’s selfless mentorship, Plymouth Governor William Bradford ordered a feast to honor the village’s new friends in the Wampanoag tribe. The tribe’s chief, Massasoit, and several esteemed members of the tribe were invited to partake in the bountiful feast as a way of giving thanks to their hospitality and generosity.

Three-Day Festival

The festival went on for three days, though the exact menu for the feast is lost to history. The pilgrims and Wampanoag might have not even used the term “Thanksgiving” to refer to the event, and much of what we know about the actual feast comes from the writing of pilgrim historian Edward Winslow, who attended the feast.

Winslow’s Account

The account of Winslow describes a peaceful, joyous meeting of two cultures. Chief Massasoit, who Winslow referred to as “their greatest king,” generously offered five slain deer to the Plymouth settlers. They, in turn, offered gifts of hunted fowl, and the two groups engaged in recreation activities which seemed to have included “exercising [their] arms,” which likely meant contests of accuracy with firearms.

The Menu

While it’s unknown what, precisely, the two groups ate at the “first Thanksgiving,” one thing is certain: they didn’t have any pies or cakes. The Mayflower had run out of sugar over a year after leaving England, and the pilgrims didn’t have any ovens with which to bake confectionary. They almost assuredly ate food seasoned with Native American spices and prepared using time-honored Wampanoag cooking methods.

The Second Thanksgiving

Here’s the one you probably haven’t heard of: in 1623, the pilgrims hosted their second Thanksgiving feast. After a long drought led them to undertake a religious fast as penance to God, the drought finally broke and Governor Bradford ordered another feast. This pattern, of fasting and feasting, became a New England tradition in the Colonial era.

Official Recognition

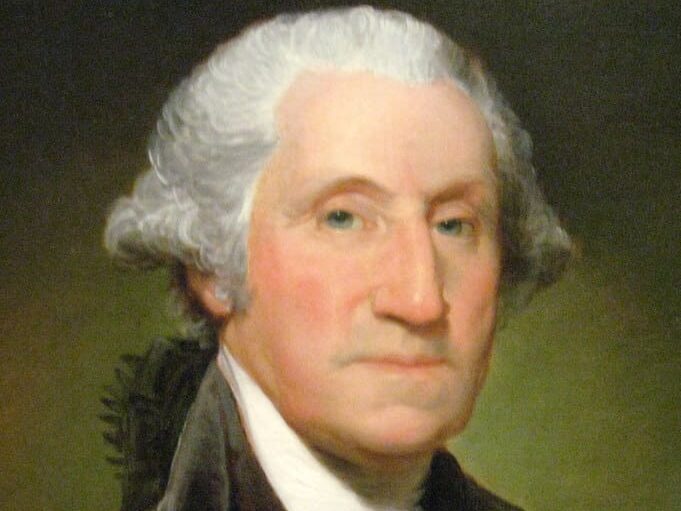

After the colonies were organized into the United States during the Revolution, several states started observing their own Thanksgiving celebrations in the fall. The Continental Congress designated Thanksgiving on various occasions throughout the newly-formed Union. George Washington issued a proclamation in 1789 calling for a national day of Thanksgiving, the first such proclamation in the Union.

Sarah Josepha Hale

It’s impossible to talk about the history of Thanksgiving without mentioning Sarah Josepha Hale. She’s considered the “Mother of Thanksgiving” due to her numerous editorials published from 1827 onward wherein she called on the US government to make Thanksgiving a national holiday.

Abraham Lincoln

Interestingly, Hale’s campaign finally became reality when Abraham Lincoln acceded to her requests in 1863 in the midst of the Civil War. Lincoln intended the holiday as a solemn reminder to “heal the wounds of the nation,” and scheduled it for the final Thursday in November each year.

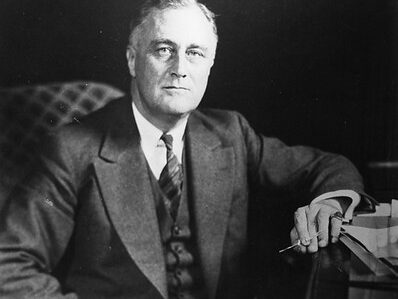

Franklin D. Roosevelt

In 1939, while the country was in the grip of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to move Thanksgiving to the third Thursday of every November to help boost retail sales around the start of Winter. “Franksgiving,” as it was known, was deeply unpopular and Roosevelt reverted his proclamation in 1941, just two years later.

The Parades

Thanksgiving is usually accompanied by parades, like the perennial Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade that started in 1924. The parade regularly brings in between 2 to 3 million onlookers to New York City who angle to get a glimpse of the historic festivities. This, like football, is a television spectacle for families on Thanksgiving Day.

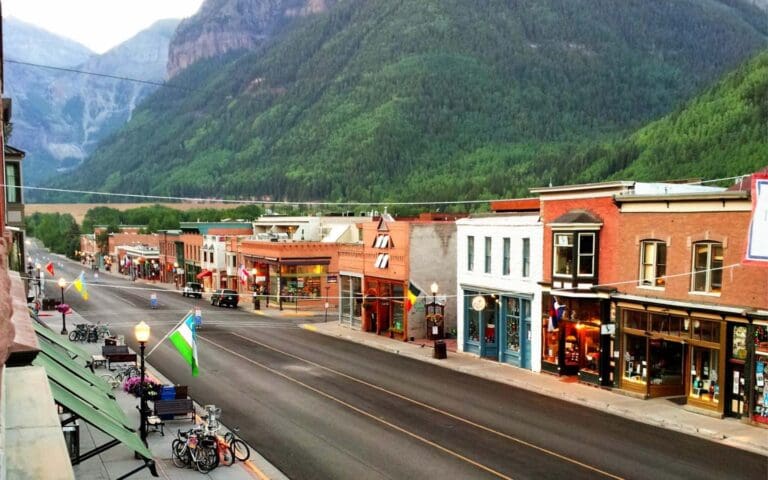

Read More: The Ultimate Guide to the Best Festival in Every US State

Pardoning a Turkey

Also, since at least the mid-1900s, it’s been a tradition for the president of the US to “pardon” a turkey on Thanksgiving, sending the bird to a farm in retirement and sparing them from being eaten by hungry people on the famous day of feasting.

Read More: 7 Actionable Ways to Beat the Winter Blues

Controversy

Some Native Americans in the modern era take issue with the way that American schools teach the history of Thanksgiving. By focusing on the unusually congenial relations between the Wampanoag and the Plymouth settlers, they argue that the traditional narrative downplays the brutal animosity between Europeans and Natives that defined the two groups’ relationship for centuries.

Read More: Ranking Each Thanksgiving Dish from Worst to Best